During the past 28 years, I have been a principal, teacher, and parent within the education system. Throughout my career, I encountered students across a spectrum of reading abilities, from those with strong reading abilities to those who struggled immensely. However, my university training and professional development had not provided me with effective strategies for teaching children to read, and I found myself ill-equipped to teach the struggling readers. I relied on the "cues" associated with a balanced literacy and whole language approach. My knowledge was confined to these approaches. I used these cues while teaching without truly comprehending why I employed them. I believed it was sufficient, and while frustrated when students' reading appeared not to ‘catch’, there was nothing more I could do.

As a school principal, I witnessed instances where both parents and teachers approached me, expressing their frustration and helplessness in assisting those struggling to read under their care. This heart-wrenching situation even extended to my son.

It is now clear to me that I could only teach in the manner I did because of the extent of my knowledge. I had never been introduced to the concept of explicit instruction, and the term itself was unfamiliar to me. Frankly speaking, I was solely focused on managing my reading groups, assuming I was doing the best job that I could. I was completely oblivious to the reality of the situation until I had my children and learning to read didn’t appear to click.

Could PHONICS be the solution? Was it the crucial element I overlooked? Absolutely not.

I was familiar with the concepts of Whole Language and Balanced Literacy and throughout my teaching career, I had instructed five-year-olds using phonics, specifically Jolly Phonics. Phonics is just one part of a much bigger picture, and this conversation is starting to get a little tired.

The crucial element was my knowledge and understanding.

If someone had asked me to explain how children learn to read, I would have struggled to be confident with my answer. I know I am not alone in this experience. Many others have shared a similar journey, lacking exposure to crucial information and explicit teaching methods throughout their years of training and professional development.

This conversation should not be about phonics, it should be about HOW we are teaching, the RESOURCES we are using to do so and the “KNOWLEDGE TRANSLATION CRISIS” (to quote Professor Pamela Snow) that has happened for far too long bridging research to practice.

Until the discovery of Multisensory Language Instruction through the Australian Dyslexia Association and then the International Dyslexia Association, as a teacher, principal and passionate parent, I had no idea how limited my knowledge and teaching practice was. We don’t know what we don’t know.

Like many teachers in Aotearoa, I was taught to teach reading using Balanced Literacy. I now teach using Structured Literacy. This video shares the key differences between the components of Balanced Literacy and Structured Literacy, but there is so much more to understand.

When I taught in a new entrant classroom, Balanced Literacy was definitely the order of the day, and this is what happened:

I taught a letter of the day where students would cut out pictures starting with the sound of the letter of the day and add them to their scrapbooks. I was unaware of explicitly linking the sound to the letter name. I did encourage children to say the sound aloud, like "mmmmmmmm," such as the sound of "marmite," while they searched for pictures to cut and paste.

I taught phonics by introducing individual and grouped sounds through catchy songs. I don't remember if we wrote down the sounds or followed a specific order when teaching them, and I didn't incorporate these sounds into words, sentences, or texts to gradually build cognitive skills, as I do now.

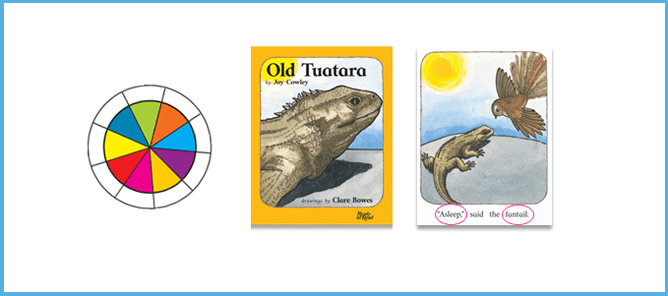

During reading sessions, I had instructional reading groups, and we used PM and Ready to Read texts, starting from Magenta/Red and progressing through the Colour Wheel levels. These texts included a mix of easy and challenging words. For instance, even in the early texts, we might encounter a word like "fantail." Although these texts were levelled, they didn't necessarily progress from simple to complex in terms of word usage. When delving into the text, we briefly predicted what might happen based on the pictures and had discussions about them. Then, we would proceed to read the text from Day 1. In fact, after reading it once, we would send the text home for students to read to their parents. Occasionally, we would read a text two or three times before sending it home. Typically, we would read a new text with words featuring different sound-symbol correspondence each day. When students struggled with a word, I used the following cues:

"Read to the end of the line, now what do you think would make sense?"

"Can you use the picture to assist you?"

"Does that sound right? Does it make sense? What else could it be?"

The assessments we used were Running Records based on the three-cueing system of M (meaning), S (structure/syntax), V (visual).

Now that I have a comprehensive understanding of how the brain learns to read and recognise the significance of explicit instruction and multisensory learning, I have completely transformed my teaching approach. My teaching follows a completely systematic, cumulative and explicit implementation. By embracing the principles and components of a Structured Literacy approach as outlined by the International Dyslexia Association, I have integrated these practices into my teaching across all classrooms I have the privilege of working in. This shift in my pedagogy stems from what we now know about both the Science of Reading and the Science of Learning, particularly through the use of explicit instruction. I now know how to best teach the students I sit across from.

It is crucial to consider the following key point in this debate

Interventions like Reading Recovery have never achieved this goal for our teaching profession. Even with a redress, “lipstick on a pig” to quote Alison Clarke, interventions of old don’t do this because their implementation methods and associated resources are still heavily centred around the ideology of balanced literacy of old.

We know reading must be explicitly taught. We want to ensure that we not only teach in a way science has determined is the most effective but also ensure that the resources used support this. Additionally, we must strive to establish an evidence-based educational pathway that remains consistent for all students. By minimising variations in the delivery of these essential foundation literacy skills, we enhance the likelihood of success for both teachers and students.

So what does my practice look like now? When you know better, you do better right?!

Teaching instruction, as previously stated, is systematic, cumulative and very explicit.

Throughout the school year, I conduct various diagnostic assessments to measure progress and identify areas requiring explicit instruction. These assessments include phonological awareness screening, spelling assessments, reading skills records (evaluating accuracy, fluency, reading rate, and comprehension), and determining the next steps in their learning journey.

Phonological Awareness is taught in a progression from simple to complex. Students learn specific skills and practice drills to enhance their reading abilities.

Spelling Instruction: I dedicate 20 minutes per day to explicitly teach spelling concepts based on assessments. I follow a structured scope and sequence that covers important spelling rules, promoting fluent reading and writing. These sessions enhance students' understanding of English orthography.

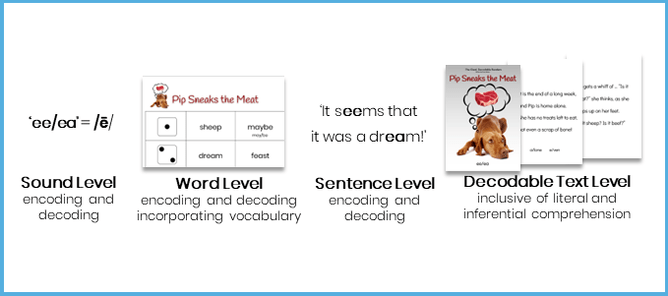

Reading Instruction: I follow a scope and sequence for beginning readers, incorporating changes from my early teaching days.

Prior to reading the text, I extensively teach students various skills, including blending sounds in words.

Students decode, encode, and decode words from the text to develop fluency and effortless retrieval of word patterns during reading.

We engage in sentence reading, writing, and analysis, including sentence structures and grammar.

I explicitly teach morphology (meaningful word parts) from the text to improve comprehension.

Once we start reading the text, my focus is on developing fluent reading through explicit instruction on accuracy, reading rate, and expression.

Some students require additional word and sentence level activities for further practice.

I teach comprehension by guiding students to extract information from the text, reducing cognitive load, and making connections between their background knowledge, vocabulary, the storyline, and implicit messages from the author.

I also teach strategies for navigating the text to accommodate varied executive functions.

When students encounter difficult words, I provide cues such as:

Focusing on the word

Identifying the first sound

Blending sounds together.

I actively engage different parts of the reading brain to facilitate learning. I recognise that some students require more time and repeated exposures. By understanding their individual pace, processing speed, and cognitive profile, I can provide support tailored to their needs incorporating ample opportunities for repetition.

The truth is, my knowledge and abilities have experienced exponential growth due to the release and exposure of the Science of Reading and the challenges I've faced as a teacher, parent, and principal. Had I continued to cling to the outdated practices of Balanced Literacy and Whole Language, I would not have acquired this knowledge. It is crucial to acknowledge that my willingness to embrace this change and information has played a significant role in this transformation. I have actively taken control of my professional development and made necessary changes to my teaching practice.

Would programs traditionally entrenched in Balanced Literacy such as Reading Recovery have undergone significant changes if the Science of Reading hadn't gained prominence and the “Reading Wars” hadn't escalated in our country? I very much doubt it.

Do these ongoing discussions feel exhausting when we find ourselves repeatedly confronting the same obstacles linked to implementing scientific knowledge while also facing opposition fuelled by deeply ingrained beliefs, established practices, and unwarranted influential approaches? Perhaps they do, but it remains crucial to persist in having them and presenting consistent evidence-based information.

While it is tempting to view Structured Literacy, decodable texts, and the Science of Reading as a "silver bullet," it is important to recognise that they are the most effective tools we have available today when implemented as intended.

The key to success lies in:

increasing teachers' knowledge in alignment with how the brain learns to read

utilising resources that support a systematic and cumulative approach to teaching reading

implementing assessment tools and intervention supports that align with these principles.

This evidence-based approach, rather than a narrow focus on phonics alone, is what truly drives successful reading instruction.