The recent Literacy Symposium in Wellington and Auckland brought together educators from across Aotearoa New Zealand to explore effective literacy teaching practices. Keynote speakers Dr Carolyn Strom, Sarah Asome, and Dr Anita Archer shared their expertise on structured literacy and evidence-based teaching. The event highlighted literacy’s crucial role in society and emphasised scalable, high-quality instruction for all students.

Learning MATTERS Consultant Ruth Blair summarised the key insights and takeaways from the speakers.

Dr Carolyn Strom: Through the Lens of Neuroscience – How We Learn To Read

Dr Carolyn Strom, a literacy specialist with a background in neuroscience, opened her presentation by addressing a fundamental question: “If research is not accessible, how can it be actionable?” Dr Strom’s presentation emphasised the importance of making the research accessible to all educators, enabling them to apply these insights effectively in their classrooms. Her remarkable ability to translate complex information into understandable terms was truly impressive. By drawing on insights from cognitive science and neuroscience, she aimed to demystify some of the most common misconceptions about learning to read.

Misconception 1: Reading is acquired naturally, like speech.

Dr Strom began by challenging the misconception that reading, like spoken language, is a natural process. She explained that while children are naturally wired for spoken language, reading is a completely different skill that requires explicit instruction. Humans have been speaking for 50,000 to 200,000 years, but we have only been reading and writing for about 5,000 years. Our brains are not naturally equipped to interpret the squiggles, lines, and dots of written language on their own. Unlike spoken language, which children can pick up through immersion and exposure, reading must be taught. We cannot rely on immersion alone to teach children to read, as most will not simply pick it up.

“Reading is taught, not caught.”

To illustrate this point, Dr Strom introduced the concept of ‘Brain City’, a metaphor she uses to explain the process of learning to read. In this metaphor, she likens the brain to a city that must build new roads (neural pathways) to connect different neighbourhoods (regions of the brain) to create a functioning reading network.

We’re born with Sound City and Meaning Mountains. Sound City represents the brain’s ability to hear and produce sounds, while Meaning Mountains is responsible for understanding language and semantics. Before students start school, we must build their oral language through Meaning Mountains and Sound City. Additionally, we are born with Vision Villages, which are wired to recognise faces and objects. However, we aren’t naturally wired to recognise letters/symbols and associate them with sounds – this must be taught.

“If a child cannot pull apart individual sounds, how can they attach sounds to letters? We are not wired for this.”

The process of learning to read involves connecting Vision Villages to Language Regions. This requires building neural pathways from vision to language and mapping letters to speech sounds. To achieve efficient reading, we need to integrate these three areas – Sound City, Meaning Mountains, and Vision Villages. As we develop reading skills, we create a ‘letterbox’ where words are stored for quick and effortless retrieval. This letterbox doesn’t exist at birth or in non-readers; it must be taught explicitly. Essentially, we are repurposing neurons to recognise letters and words.

A child’s vocabulary and spoken language are strong predictors of future reading ability, so we are laying the essential groundwork now to prepare them for the code.

Misconception 2: Learning to read is primarily a visual memory process and starts with memorising the shape of a word.

We need to build efficient reading pathways between vision and language, and this must start early. Waiting to identify and intervene can lead to a ‘wait to fail’ scenario. Prevention is far less costly, both financially and emotionally, than intervention. While learning to read is always possible, the optimal time for instruction is between ages three and eight, when the brain is most adaptable (with optimal plasticity).

My brain is plastic, so fantastic

Just like elastic, change can be drastic!

The more I learn, the more my brain changes…

And rearranges!

One crucial point is that the vision system must unlearn ‘mirror invariance’, which involves retraining neurons to correctly recognise letters like b, d, p, and q. This process is a normal part of development and does not indicate dyslexia. The best approach is to practise writing and forming these letters correctly, as repeated practice helps solidify these skills. Some children need many opportunities to practise this correctly. Practice makes permanent.

Mapping and blending letters are distinct processes. “Neurons that fire together wire together.” The phonological pathway that connects vision to language is the foundation pathway to reading. This pathway, although slower, is essential and requires years of spaced and interleaved practice. The more practice on this route, the faster this will allow for automaticity to the letterbox. This more direct route is called the lexical route. When children are reading at about 120 wpm they are on their way to automaticity. Typically, by the age of seven, children are moving towards this level of automaticity, and this is when self-teaching begins. If we don’t develop the letterbox, children will struggle. Once it’s there, Working Memory and Attention Antennae are freed up to focus on other things.

Reading and writing are two sides of the same code. As we are building this city, it’s important to ensure that students are both decoding (reading) and encoding (writing) in each lesson. Starting from age three, we can incorporate gross motor movements to help children think about how letters are formed, supporting their literacy development.

Misconception 3: Structured literacy leads to a ‘drill and kill’ mind set

Addressing concerns that structured literacy is overly rigid and dull, Dr Strom argued that structured literacy can and should be engaging. She acknowledged that repetitive practice is necessary for learning, much like in sports or music. However, she emphasised that this practice doesn’t have to be boring.

Dr Strom’s mantra, ‘drill and skill with a thrill’, encapsulated her belief that effective literacy instruction should be both systematic and engaging. She advocated for using a variety of activities that make learning fun while reinforcing essential skills, by incorporating engaging routines, like KPTs (kitchen table practices), easy games such as “I Hear with My Little Ear” to tune into sounds, embedded mnemonics, and our favourite “Fiddle in the Middle” (IYKYK).

Sarah Asome: Alignment of Practice Across the Tiers

Sarah Asome, Principal from Bentleigh West Primary School in Australia, shared her insights on the importance of consistency and clarity in literacy instruction. Sarah provided a detailed overview of how Bentleigh West has achieved success in literacy through structured, evidence-based teaching practices.

Sarah brings extensive experience in early screening, teaching, and intervention. At Bentleigh West, they began with a focus on both content (influenced by Yoshimoto School) and delivery (guided by Associate Professor Lorraine Hammond). Their teaching model for English uses Structured Literacy delivered through Explicit Direct Instruction (EDI). Understanding how the brain learns to read is well-established, and their approach reflects this research. They emphasised a gradual rollout, adhering to the principle that “if we want something done well, we have to give time to it.”

Bentleigh West is renowned for its high performance and exceptional outcomes, driven by a strong foundation of research and evidence. The school is committed to ongoing professional development and prioritises student voice and agency, ensuring that students understand how and why they learn and the significance of retrieval practice. Their approach includes daily, spaced, and interleaved reviews of concepts, integrating regular practice across multiple topics.

The curriculum is pitched 12 months in advance, with a well-structured literacy block that initially breaks down activities into specific time slots (e.g., 5 minutes for phonological awareness and 15 minutes for handwriting) until teachers become familiar with the routines. Instead of separating reading and writing, the literacy block combines these elements into a cohesive lesson structure, including daily reviews, phonics, morphology, handwriting, spelling, fluency pairs, and English lessons. Fridays feature a weekly content review through mini quizzes, which inform the following week’s review.

The school day begins calmly and quickly, tackling the most challenging learning in the morning. Throughout the years, they provide consistent structure and scaffolding while avoiding excessive homework, recognising the hard work students put in during the day. At Bentleigh West, teaching content is inseparable from teaching reading.

Instruction model:

Consistency is crucial. At Bentleigh West, every aspect of teaching – from lesson planning and classroom displays to reports and time on task – is designed to maintain low variance and achieve high outcomes. Key focus areas include:

classroom layout: seating arrangements in rows, paired sharing partners

attention: minimising visual distractions school-wide

pace: adopting a ‘go slow to go fast’ approach

vocabulary: explicitly teaching new words

assessment schedule: moving away from pre- and post-testing

leadership: conducting regular observations and walk-throughs

whole class instruction: ensuring all students receive high-quality instruction rather than busy work or distraction during rotating group activities. This approach requires time and practice for teachers to master.

Engagement norms are consistently applied throughout the school using the TAPPLE framework, which includes attention signals, ‘wipe it’, ‘park it’, ‘hover’, ‘chin it’, volunteer picking, and warm/cold calling.

Sarah highlighted the importance of daily reviews and practice, which help reinforce learning and build automaticity. Each day, students participate in activities that review previously taught skills and introduce new concepts. This daily practice ensures that students have the opportunity to master essential reading skills.

At Bentleigh West, the pace of learning is fast, with a high level of preparation and practice required from teachers. Staff consistency in practice and delivery is vital. As Sarah quoted Associate Professor Lorraine Hammond, “You’re not self-employed.”

Alignment of Tiers 1, 2, and 3:

“Fewer than 1 in 5 students who are behind by Year 4 catch up and stay caught up.”

Effective systems and structures are essential across all tiers of support:

Tier 1: Provides consistent, high-quality teaching with a well-mapped curriculum pitched 12 months in advance, ensuring low variance and high outcomes. For example, year 2 are working on year 3 content.

Tier 2: Students needing additional practice receive aligned assessments, extra support 2–3 times a week, and regular progress monitoring.

Tier 3: For students requiring intensive, individual support, Occupational Therapy (OT) and Speech and Language Therapy (SLT) are involved. All teachers are trained to deliver and support Tier 3 interventions.

Additionally:

Preschool Screening: Conduct screenings in October for the following February to identify early needs.

Leadership Meetings: Hold fortnightly meetings to discuss which students may need to move to Tier 3.

Where to begin?

Sarah stressed the importance of starting small, as attempting to implement everything at once can be overwhelming and they have been on this journey now for some years. Sarah recommended beginning with foundational areas, such as spelling, and ensuring that all staff are upskilled through ongoing professional development (PD), with a structured plan in place for new staff.

She also emphasised the need for careful recruitment to build the right team and highlighted the importance of meticulous budget management. Sarah advised choosing PD wisely, noting that not all PD is equally effective.

Dr Anita Archer: Engaging Every Learner – The Power of Active Participation

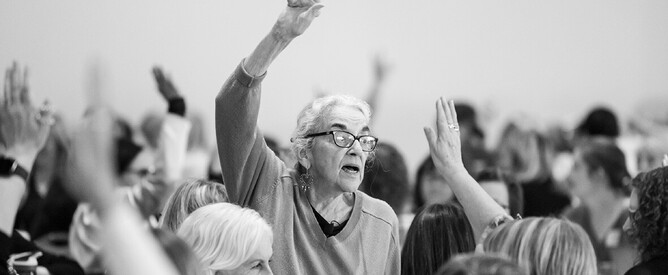

When Dr Anita Archer speaks, the educational world listens, and the symposia were no exception. Dr Archer had the crowds in Wellington and Auckland fully participating in her engaging sessions.

She underscored that “good instruction is actively participating” and highlighted key elements:

Opportunities to respond

Getting them all engaged

Learning is not a spectator sport

Dr Archer emphasised that learning is not a passive activity; students must speak, write, and do things every day in every class. This approach ensures that every student is involved, avoiding the common pitfall of only engaging a few. “Everyone does everything.”

The most inequitable practice is when: Teacher asks a question, hands go up, teachers call on a student. Who is going to put their hand up? That is teaching the best and leaving the rest. As Dr Archer stated, “Education is not for some; it is for all.”

No matter the subject – be it Art, PE, Science, Maths, Social Studies, or Literacy – the explicit instruction cycle remains consistent: Input, Question, Response, Monitor, Feedback, and Adjust.

Dr Archer emphasised the importance of this rhythmic cycle in delivering effective instruction. “There is a constant rhythm of instruction embedded in this. This is essential in terms of the delivery of instruction. You can have good content, but if not delivered in a way where students are present and responding then learning would be different.”

What are some ways we can ensure students are actively participating in class?

Structured Choral Responses: Use choral responses for short, uniform answers. Provide a cue for the class to respond together and redo if necessary. Ensure ample thinking time for all students.

Choral Reading: Implement choral reading where the whole class reads together to enhance engagement.

Cloze Reading: Incorporate cloze reading exercises, where students fill in missing words, to encourage participation.

Partner Work: Assign students as partners (ones and twos) and teach them techniques like ‘look, lean, whisper’. Clearly define roles and directives for each partner and have them prepare before sharing with the class. Change partners regularly to promote diverse interactions.

Individual Responses: Have students prepare their responses and share them with their partners before calling on individuals. Use a random selection method, such as drawing names from ice block sticks, to ensure fair participation.

Why is it important to frequently elicit responses from students?

Boosts Engagement: Regularly asking for responses keeps students actively involved in the lesson.

Enhances On-Task Behaviour: Frequent interaction helps students stay focused and attentive.

Increases Accountability: Regularly responding holds students accountable for their learning.

Encourages Desired Behaviours: It reinforces positive behaviours and participation.

Reduces Inappropriate Behaviours: Keeping students engaged helps minimise distractions and off-task behaviour.

Frequent responses help keep the class dynamic and prevent gaps in engagement. As the saying goes, "Avoid the void, for they will fill it."

Let’s explore three key reasons for frequently eliciting responses:

Practice and Retention: When students are required to respond, they engage in active practice of the content. This focus helps them rehearse, retrieve, and ultimately retain critical information. The process is simple: REHEARSE. RETRIEVE. RETAIN.

Formative Assessment: Eliciting responses provides valuable feedback on students' understanding. It allows teachers to monitor progress and adjust instruction as needed. A critical aspect of effective teaching is maintaining a clear ‘teaching arena’. Teachers should focus on teaching during instruction and only move around the room to monitor and provide feedback when students are working independently or with partners.

“This one is really critical. I teach teachers to teach from a teaching arena. This is what I see happening a lot – teachers monitoring around the room and trying to teach at the same time. Then the students are searching around the room – where is the teacher? I teach teachers to go back to their teaching arena when they are teaching. If the students are sharing something with their partner or writing on their whiteboard or book, only then is the teacher moving around monitoring and giving feedback.”Targeted Feedback: Regular responses enable teachers to offer immediate feedback, including praise, specific praise, and necessary corrections, both to individuals and groups.

“Walk around. Look around. Talk around.”

This mantra emphasises the importance of being engaged and observant in the classroom to ensure that learning is actively taking place. As educators, our careers are dedicated to facilitating learning, making the delivery of content just as critical as the content itself.

Research shows that providing students with opportunities to respond increases their time on task, enhances learning, reduces disruptive behaviour, and intensifies the effectiveness of interventions. High-performing teachers create three–five opportunities for student responses per minute, such as speaking together, using gestures, or holding up response cards. Aiming for at least one response per minute is a good benchmark.

“Instruction that is good, is interactive. We give input, we ask a question, they give a response, they monitor, we give feedback and adjust our lesson.”

So, what is essential? There are FIVE BIG IDEAS that Dr Archer would look for in any classroom, focusing on delivery and opportunities to respond. These are low prep but high outcome strategies:

Request Frequent Responses from Students: Engage students consistently to keep them involved and attentive.

Require Overt Responses: Encourage students to respond by saying, writing, or doing something.

Involve All Students: Adopt a no-opt-out, no-hands-raised policy. Everyone participates fully. This avoids the inequity of traditional questioning where only a few students dominate.

“If you want to change something at your school that is the least equitable practice at your school it is, I ask a question, you raise your hand, I call on oh gifted one, they say a brilliant answer and I move on. That is inequitable.”

Structure Active Participation: Assign partners and numbers to ensure equitable participation. For example, in ‘turn and talk’ activities, one student often dominates the conversation, which can lead to inequitable participation. To create more balance, assign numbers to partners – Partner 1 shares with Partner 2, and then they switch. Encourage students to respond in complete sentences, and provide sentence stems to guide their answers.

“Equity is all in our actions. I’m looking for the little things we do across all students.”Provide Adequate Think/Prep Time: Give students time to think and prepare their responses, ensuring more thoughtful and meaningful participation.

“Our job as teachers is to set students up for success. The key to success is motivation.”

Clarity, clarity, clarity. Practice, practice, practice. Woo woo woo woo!

Dr Archer’s final inspiring words:

“Here’s what I can guarantee you about Structured Literacy being implemented at a high level in your country – especially if you're working in early childhood, NE-Y3. The first thing you will notice is a significant reduction in the number of students referred for any kind of intervention. Wouldn't that be a good thing for them? That you’ve taught it so well they can go forward. If you continue this through the first eight years, you will have children entering high school being able to read and write. The benefits are immense. The biggest benefit is that to be able to read and write at a high level is a civil right – in the United States, in Australia, and in New Zealand.”