English is a complex language and although we are wired to learn to speak, we are not wired to learn to read or write. We must be taught.

I must admit when I began my teaching journey some 26 years ago, I don’t believe I recall wondering let alone learning about how we learn to read. I was young and trusted the knowledge that was imparted on me by my lecturers of the time at university. I am sure that many teachers will have been, and may still be, in this same boat. This blog sets out to help parents and teachers understand why reading instruction looks like it does in various classrooms across New Zealand.

So don’t all teachers teach reading in the same way?

The answer to this question is no, they do not. The truth is there is a lot of variability across schools. It can also differ from teacher-to-teacher within a school.

Hence, the lottery of reading instruction.

As parents, when we send our children to school it would be reasonable for us to think that our child will be taught to learn to read in a way that is informed by the best scientific evidence. But for some schools, (unintentionally), this isn’t the case.

As Professor Pamela Snow stated during a recent Chit Chat, “one of the biggest issues is that we seem to have landed in many cases on something called Balanced Literacy.”

“The problem is that Balanced Literacy really grew out of an approach called Whole Language.”

She continues to explain that this approach during the 1980s, “was adopted with a lot of enthusiasm and not a lot of critical analysis in countries like Australia and New Zealand” and unfortunately, “Whole Language had as an underlying principle the idea that learning to read is as natural as learning to speak, and we know that that’s not the case.”

Further to this Pamela states, “the way we teach reading has been controversial for some time.”

As an example, let’s talk about levelled readers, which are used in a Balanced Literacy approach. When accessing these texts as a novice reader, it may look as though your child is reading, but generally, they are reciting repetitive sentences (and looking at the pictures for cues). Their eyes are not on the text at all, they are not learning transferable skills. They are in fact reciting and they are guessing – they are not reading. It’s an illusion.

Many of our teachers have been trained to teach in this way, so it is no fault of the schools or teachers. When we advocate for a shift to evidence-based practices, this not only needs to happen in how children are taught to read, but it also needs to occur in how our teachers are taught to teach reading.

One of the biggest differences in these approaches is the move from using a levelled text (which has a range of sounds and letter combinations and words) to using a decodable text which follows a systematic scope (content) and sequence (order).

Balanced Literacy is currently engrained in many of our schools. This approach does not align with the findings from neuroscience, cognitive psychology, linguistics, or educational research that forms a body of research termed the Science of Reading (the largest body of international reading research).

All too often I hear myself saying … “when we know better, we do better.”

For many years we have known that ALL brains learn to read in the same way. The research conducted by cognitive psychologists, neuroscientists and linguists has struggled to make its way onto the classroom or university (teacher training institutions) floor. The space of course we really need it to land.

As discussed in the chit chat with Professor Pamela Snow there has been a knowledge translation crisis. We have experienced a lag of information being presented to the education sector and all the while an ideology of how we learn to read became embedded. This coupled with some clever quote-mining has allowed a continuation of a Balanced Literacy approach which encourages our children to look at pictures, guess at words and not be taught in a logical way from simple to complex.

On the contrary, let’s look at the principles of instruction adhered to by schools who now know better. By schools who are committed to an evidence-based approach for ALL:

- Diagnostic - Instruction is Diagnostic through gathering assessment data in phonological awareness and alphabetic principle (foundation literacy skills).

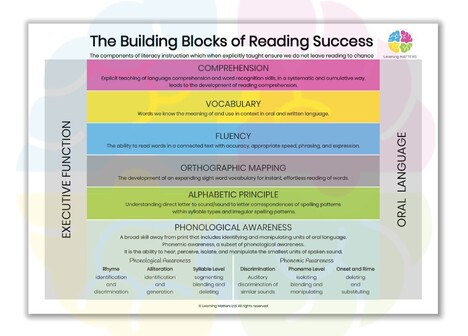

- Systematic - Instruction is Systematic and is taught in a logical order from easiest to most difficult. It needs to build on the blocks of reading success (image below) starting with the foundations being secure and not making assumptions that children will be able to read a book simply because they have been exposed to it. Children don’t have a magical sleep the night before they turn 5, they do not become readers overnight. This takes time and requires explicit teaching of set skills in a logical order.

- Cumulative - Instruction is Cumulative as teaching builds step by step on concepts previously learned. If we can read and write the following sounds s,a,t,I,m,n,o,p,b,c,g,h then we will be taught to read and write words and sentences and texts made of these. We then build on that by adding onto those letters and sounds and more and more we begin to open up the amount of language, code and vocabulary our children can read and write. This is not to be mistaken as the only exposure to oral language. All the while our children continue to be spoken to and read to across a range of texts. This helps their brain prepare for when they do come across this language in written form.

- Explicit - Instruction is Explicit, intentional, and multisensory. We teach in a way that as Dr Anita Archer would say … “children get it”.

Hence the term Structured Literacy.

A Structured Literacy approach intentionally moves slowly and builds up over time, ensuring we help our children to develop the ability to lift words off the page and onto the page when writing. It enables the cognitive load in the brain to be freed, to then access further learning. It does not leave reading and writing to chance.

This approach preserves and fosters success and confidence.

There is no pendulum swing here. The science is clear. If we are going to use the term balance any longer in literacy circles it MUST only be to explain that in a Structured Literacy approach, where we teach both word recognition skills and language comprehension. This is the only place any mention of balance belongs. We need structure to these two components. Developing automatic word recognition skills in the first three years of school frees up a child’s ability to be able to focus on using reading as a skill to access the curriculum. What we experience when reading (decoding) has not become an automatic skill is frustration, low self-esteem, disengagement, and despair. This can and must be avoided through quality and structured early teaching.

We cannot wait for our children to fail.

“It takes four times as many resources to resolve a literacy problem by Year 4 than it does in Year 1.” Dr Kerry Hempenstall

Let’s ensure we have a tight safety net. And that safety net is a current research and evidence-based Structured Literacy approach.

What do I need to look out for?

So as a parent of a young child (or a not so young child) I encourage you to open up the discussion of how reading is and has been taught to your child. Whilst we are making great inroads, reading instruction in New Zealand is still somewhat of a lottery. We want to ensure your child’s odds are increased by equipping you with the right questions to ask when chatting with your school leaders and classroom teachers. Remember when we know better, we do better, so step one is raising awareness then building knowledge and shared understandings.

Tread kindly – all teachers I know go to school with a big heart and to do their very best, it’s not their fault, just like it wasn’t mine, if they weren’t taught what they should and could have been.

- Build your knowledge of teaching foundation literacy skills.

- Beware of Balanced Literacy this is such a ‘different beast’ from Structured Literacy and if implemented may do more harm than good for your child, particularly if they are at risk of being, or are neurodiverse.

- Beware of phonics as an independent way of teaching. Phonics as a clip-on in a literacy block (that then uses levelled books for novice or struggling readers that encourage guessing) is not useful.

- Beware of a limited structured approach, a ‘monster dressed as a princess’ as I call it. Ask questions about the scope and sequence being used and the alignment of decodable texts for novice and struggling readers.

- Linking schools to similar schools that have been on a ‘guided implementation and practice improvement process with a literacy coach, specialising in Structured Literacy implementation.

- When discussing with teachers/principals point to the facts and share trusted links and articles.

As a parent myself I really do wish I had all this knowledge and insight way back when. As a professional I am working hard to pave the way for this much-needed improvement across our schooling sector. I can’t change the trajectory for my son or the children under my watch in the past, but I can certainly continue to work to shape a different pathway and raise awareness for you and your tamariki. Are you with me on this journey?

Further reading and information:

Check out our Leap into Literacy webpage. This page provides bite-sized and practical foundational literacy activities you can do with your children. These activities are based on the Building Blocks of Reading Success, which highlights the key elements that must be taught for reading success.

During our Chit Chat Pamela Snow pointed to the following article to help you fill your knowledge kete: https://www.apmreports.org/episode/2018/09/10/hard-words-why-american-kids-arent-being-taught-to-read

Carla McNeil

Carla is the Founder and Director of Learning MATTERS Ltd. Carla has been a successful School Principal, Mathematics Advisor and Classroom Teacher.